Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip: The Complete Series (Warner Home Video)

Video and DVD

By Steven Rosen . . . . . . .

STUDIO 60 ON THE SUNSET STRIP: THE COMPLETE SERIES

2006, Not Rated

Aaron Sorkin's screenplay for The Social Network is probably going to get an Oscar on Sunday, and deservedly so. But the previous accomplishment by this writer, who knows how to tackle topical ideas about the role of media in society and offer complex, compelling characters, has been unjustly overlooked. Hopefully, Social Network will encourage people to take a second look at Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip -- a great series.

As they did with Lisa Kudrow's superb but ill-fated The Comeback, wrong-headed TV critics attacked the daring Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, Sorkin's knowing, brainy and fantastically-acted follow-up to the The West Wing. They labeled it "pretentious" and "not funny enough." As a result, the show never got the buzz it needed to be a success, and NBC canceled it after its first season.

It's a great loss. This drama -- it's not a comedy -- ostensibly is about the struggle of two head writers/producers (Matthew Perry and Bradley Whitford, both excellent, with Perry a revelation) to put on a weekly Saturday Night Live comedy show.

But that's just the window into Studio 60's real subject -- the ethics, policies and politics of network television. And, next to the White House, what better institution for Sorkin's lacerating, fast-paced and quick-witted writing style? The best of these 22 episodes include sizzling, literate, argumentative back-and-forth among Perry, Whitford, Steven Weber as the network chairman and Amanda Peet as the network president. Grade: A

(Adapted from Cincinnati CityBeat)

Share

Monday, February 21, 2011

Saturday, February 19, 2011

Film Review | The Last Waltz (1978)

And the Band Played On

by Thomas Delapa

Was the greatest American rock ‘n’ roll band, gulp, (mostly) Canadian?

Before you start waving Old Glory or invoke the Patriot Act, consider the case of the Band, one of rock’s most influential groups and arguably the most musically virtuoso. If the Doors, the Grateful Dead and the Beach Boys represented the cream of West Coast classic rock, the Band was the best from the American Heartland.

Whatever your affections, the Band’s The Last Waltz still may be the last word in rock-concert documentaries. An exuberant, star-studded record of the band’s 1976 farewell concert, it’s one rockumentary that still rolls, nearly 35 years later.

On San Francisco’s famed Winterland stage on Thanksgiving Day, the Band got together to say goodbye after 16 years as a group. Among Canadians Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel and Garth Hudson, Arkansas-born Levon Helm was the lone Yank when they were first incarnated as the Hawks. It wasn't until the mid-sixties that “the Band” moniker stuck, and by then they had emerged as Bob Dylan’s backup group. Robertson (guitar) and Helm (drums) were with Dylan at his tumultuous Forest Hills, N.Y., concert in 1965, when he shocked his folkie fans by plugging in and going electric.

It was during those heady days that Dylan and the Band collaborated on one of rock’s most celebrated underground recordings—eventually released as The Basement Tapes in 1975. In 1968, the Band came out with their heralded debut album, Music from Big Pink, containing such signature tunes as “The Weight.”

As rock critic Greil Marcus once wrote, the Band “brought us in touch with the place where we all had to live.” No other U.S.-based band was so immersed in such an eclectic array of musical sources. Rockabilly, country, the blues, jazz, gospel—and classical—were among their touchstones; in retrospect, they also formed the leading edge of burgeoning “country rock,” along with Creedence Clearwater Revival and the Allman Brothers. The Band’s roots in bygone musical Americana go way back, so deep that one critic observed that they were the only rock group that might have played at Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration.

And now we can be nostalgic about the Band, which has sadly unraveled since its official 1976 swan song. A long-running feud between Robertson and Helm (over songwriting credits) resulted in Helm’s absence when the group was inducted in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994. Rick Danko died in 1999, while Richard Manuel took his own life in 1986.

What remains, as always, is the art and music, and fans should be grateful that director Martin Scorsese conducted The Last Waltz with a polished, first-class elegance, shooting it like a feature film with multiple 35mm cameras. Scorsese—then in the midst of his own triumphs with Taxi Driver and Raging Bull—sandwiches the 20-odd songs with brief backstage interviews with the band members, a pool table and a Confederate flag acting as dissonant backdrops. Scorsese’s own backup included a trio of star cinematographers in Michael Chapman,Vilmos Zsigmond and Laszlo Kovacs.

What gives The Last Waltz its shake and shimmy isn’t just the songs but the cavalcade of guest stars that are practically a primer of three decades of popular music. While Neil Young, Dr. John, Emmylou Harris, Paul Butterfield, Eric Clapton, Joni Mitchell, Ringo Starr, the Staples Singers, Muddy Waters and, yes, Neil Diamond all drop in, it’s a spangled Van Morrison who burns up Winterland, pumping up the volume on “Caravan.” To top it off, a cool Dylan strolls in for his own fancy footwork, leading the ensemble in the anthem-like “I Shall Be Released.”

The Last Waltz was released on DVD in 2002, and includes a commentary track by Scorsese and Robertson, bonus footage and a "making-of" featurette.

-------------

2/19/11

Saturday, February 12, 2011

Groundbreaking PBS Documentary Out on DVD

Couch potato

DVD review

By Steven Rosen

(From Cincinnati CityBeat, 2-9-11)

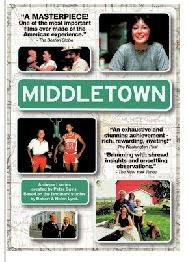

MIDDLETOWN (ICARUS FILMS) 1982, Not Rated

Middletown, a 1982 PBS documentary series about everyday life in Middle America — Muncie, Ind., where Robert and Helen Lynd based their landmark 1929 sociological book, also called Middletown — has had a troubled history.

Produced by Peter Davis — who had won an Oscar for the critical Vietnam War documentary Hearts and Minds and written a book, Hometown, about life in Hamilton, Ohio — it was meant as a return to the searing, revelatory, verite-style reality television that PBS pioneered with 1973’s An American Family.

That it was, as Davis and other directors looked with precision and empathy at such subjects as hometown politics (“The Campaign”), religion (“Community of Praise”) and divorce and re-marriage (the lovely “Second Time Around”).

That it was, as Davis and other directors looked with precision and empathy at such subjects as hometown politics (“The Campaign”), religion (“Community of Praise”) and divorce and re-marriage (the lovely “Second Time Around”).

But the final episode, the two-hour “Seventeen,” directed by Joel Demott and Jeff Kreines, turned out to be a hot potato — or, maybe, a hand grenade. In dealing very frankly with a group of Muncie Southside high school seniors, it unnerved PBS with its talk of sex and drugs, its depiction of tense interracial relations and the foulmouthed disrespect the students showed their teachers. It starkly showed how public education can fail.

After advance-screening it in Muncie, PBS canceled its broadcast amid heated, angry charges all around. Davis was able to show “Seventeen” in limited theatrical release, and it even won a 1985 Grand Jury Prize at Sundance for best documentary. But it has never been widely available until now, released with the five other Middletown episodes on a four-disc set, with a 16-page booklet featuring a new essay from Davis.

“Seventeen” is daring, but looking back almost 30 years later, it’s painful to watch. That might be why Davis reports in the booklet that most participants are reluctant to talk today. But Middletown does constitute an important chapter in TV-documentary history, and it’s good to finally have it available.

Grade: B

Friday, February 11, 2011

Film Review | Biutiful

Biuty and the Beast

by Thomas Delapa

The Mexican-born director Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu isn’t much on subtlety. The doleful life portrayed in his latest globalized drama, Biutiful, is anything but beautiful. Despite a pretty fine performance by Javier Bardem, dramatically Biutiful is less than skin deep.

Oscar-nominated for his lead role as Uxbal, Bardem is a conflicted Barcelona grifter who deals in the ugly business of human trafficking. As shady middleman, he procures illegal Chinese immigrants for his brother’s construction jobs. Uxbal also has his dirty hands in the exploitation of drug-dealing African immigrants, who are continually rousted off the street by the Spanish police.

Through the prism of jagged, herky-jerky storytelling we’ve seen before in Inarritu’s Babel and 21 Grams, we glean that Uxbal is one hombre with mucho problems. He’s separated from his needy, bipolar wife (Maricel Alvarez). He tries to be a good father to his two kids, but they’re a handful, especially at dinnertime. (The film’s title comes from his daughter’s misspelling of “beautiful.”) But most dire, Uxbal’s doctor shocks him with the news he has prostate cancer. At night he anxiously stares at his stained ceiling, pondering his fate and misspent life.

The glum underworld flip-side to Woody Allen’s Vicky Christina Barcelona (which Bardem also starred in), Biutiful isn’t on any tourist map, except for ironic glimpses of Gaudi’s famed Church of the Holy Family off in the distance. Looming larger are factory smokestacks seething black plumes. This is a place of squalor, crime and corruption, where Uxbal’s cancer is nothing if not a creeping metaphor of a sick and impotent culture that feeds on its young.

Inarritu is a tricky director, hiding his blunt, post-colonial themes under a veneer of grubby naturalism. Like Babel, Inarritu’s picture of the Western world is so biblically decadent and diseased, death appears as the only just way out. Few rays of hope shine in this hell, one falling on a beatific black immigrant (Diaryatou Daff) whom Uxbal redemptively tries to stake to a new life.

As a dirge for a doomed man, Biutiful makes Leaving Las Vegas look like Sleepless in Seattle. Inarritu and his cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto are determined to make us recoil in horror, sorrow and pity. Uxbal exhumes his dead father’s decaying body to say his final goodbye. Step by Golgothan step, we chart Uxbal’s bathroom miseries as the cancer progresses. To make sure we have a Joseph Conrad anti-epiphany (“the horror, the horror”), we witness what happens when you mix a room full of sleeping Chinese laborers and a cheap heater.

In this cadaverous exercise in cultural self-flagellation, Bardem marches on, treated like a lab rat forced into a meat grinder. We dutifully expect (and get) scenes of Uxbal’s potential atonement—along with obscure visions of an afterlife—but this is a character far less deserving of otherworldly redemption than a down-to-earth judge and jury.

--------------

2/10/11

Thursday, February 3, 2011

Film Review | No End in Sight (2007)

The Blind Side

by Thomas Delapa

Hindsight may be 20/20, but in the case of the Iraq War, No End in Sight clearly deserves a second look.

Director Charles Ferguson ended his eye-opening 2007 documentary on the eve of the American “surge”—a time when the Iraq occupation was looking like an interminable, Vietnam-style quagmire. Today, while U.S. military operations there have officially ended, some 50,000 American troops remain, and the government's battle against violent, sectarian insurgency remains an ongoing campaign.

Neo-revisionists looking for a way to resurrect George W. Bush’s moribund presidential legacy won’t find any ammunition in this major post-mortem. While Ferguson’s interview subjects run the range of the political spectrum, a consensus appears that America’s overall war strategy was (pick one or more): “a fool’s errand,” “a grave error,” and “we did almost everything wrong.” Perhaps we should go as far to quote former Bush Secretary of State Colin Powell, who once ominously warned of U.S. intentions in Iraq: “You break it, you own it.”

Ferguson delves primarily into the U.S. postwar strategy following President Bush’s infamous “Mission Accomplished” proclamation in May 2003. Many high-level participants— such as senior occupation officer Col. Paul Hughes—seem to agree that American mistakes revolve around three fateful decisions made immediately thereafter: 1) the decision not to declare martial law in the wake of looting and disorder in Baghdad; 2) the wholesale, indiscriminate “de-Ba’athification” that purged the Iraqi government of skilled workers and bureaucrats; 3) the decision to disband the Iraqi army. With regard to the latter, some in the military (which might have been utilized to keep order during the occupation) instead ended up fighting in the insurgency as part of anti-U.S. militias.

If there’s a nonstop theme in No End in Sight, it’s that the Bush administration utterly failed to formulate an adequate plan for the occupation and reconstruction in the aftermath of all that shock and awe. Winning the war was relatively easy. Winning the peace remains as elusive as the search for Saddam Hussein’s WMDs.

While rueful experts such as Hughes and former U.S. Ambassador Barbara Bodine were either marginalized or fired, and many Pentagon policy recommendations were ignored, the Bush/Cheney/Rumsfeld White House instituted a top-down, take-no-prisoners approach, for instance vastly underestimating the total number of troops needed for the occupation. Not-so-fun fact: In World War II, the Allies devoted two years on a strategy for the German occupation; by contrast, the Bush White House spent less than two months on a plan for postwar Iraq.

For those willing to reconstruct these crucial events, No End in Sight recoils with biting sound bites that tragically refute what we now know. Way back in 2005, Vice President Dick Cheney declares that Iraq was in “the last throes of insurgency.” Likewise, at a 2003 press conference, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld flippantly states that he “doesn’t do quagmires.” And in Famous Last Words department, Arlington division, in 2003 Bush scoffs at talk of an insurgency with a bellicose “Bring ‘em on.”

With the estimate of the war’s overall cost (including veterans’ care) escalating to well over $1 trillion, American taxpayers are still pouring it on. This is a far cry from Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz’s rosy 2003 pitch that Iraq’s reconstruction would pay for itself, the cost offset by gushing Iraqi oil revenues. To date, over 4000 U.S. soldiers have died in Iraq, along with at least 100,000 Iraqis. Some three million Iraqis have fled their country.

Contrary to Bush administration predictions, the Iraq War has been no magic carpet ride. One expert even goes as far to say that the war and the chronic Iraqi national instability have actually been instrumental in “reviving radical Islam in the world.”

While the outcome of the tumultuous current events in Egypt are far from certain, recent social revolutions—as in the case of the Soviet Union—have shown time and again that history must take its course, and that the ultimate end to despotic regimes must lie in the power of the people, not in disastrously myopic superpowers.

------------

2/2/11

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)